Commentary on David Roodman's "Modeling the Human Trajectory"

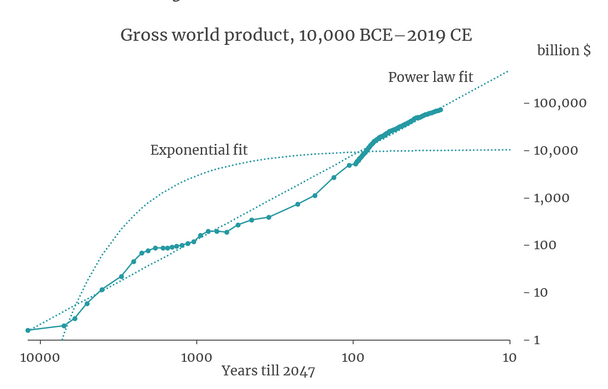

David Roodman’s Modeling the Human Trajectory, a report created for the Open Philanthropy Project, provides a perspective on humanity’s economic and technological history and where we may go in the future. To coarsely summarize the report’s thesis: The economy appears to be growing hyperbolically, and if we continue on this path, the economy will be infinitely large by the year 2047.

Disclaimer: I read the Open Philanthropy blog post, but I have only briefly skimmed the full technical report, so my interpretation could be missing something.

This result comes from the observation that economic growth is accelerating. Roodman presents this graph to illustrate:

Roodman writes the following about hyperbolic growth:

Cyberneticist Heinz Von Foerster and colleagues highlighted this implication in 1960. They graphed world population since the birth of Jesus, fit a line to the data, projected it, and foretold an Armageddon of infinite population in 2026. They evidently did so tongue in cheek, for they dated the end times to Friday the 13th of November. As we close in on 2026, the impossible prophecy is not looking more possible. In fact, the world population growth rate peaked at 2.1%/year in 1968 and has since fallen by half.

Pay particular attention to the last sentence of this quote, where Roodman notes that the hyperbolic growth predicted by Heinz Von Foerster has leveled off—growth has not accelerated since 1960, and in fact has declined somewhat.

(This is discussed in a Slate Star Codex article, which Roodman links to.)

Although Roodman addresses this point, I believe his article somewhat under-appreciates it, so I want to emphasize it. The central thesis of his report (at least by my reading) is that the growth trajectory of civilization projects infinite economic/technological growth in finite time, and that this says something meaningful about the future of humanity (although, as he writes, it’s not at all obvious how we should interpret this observation). But I do not believe we can fairly say that the history of civilization does in fact project hyperbolic growth.

The article fits a hyperbolic curve to historical gross world product (GWP) and finds that it predicts infinite GWP by year 2047. What would have happened if we had run the same analysis a few years ago, say, in 1960 or 1980?

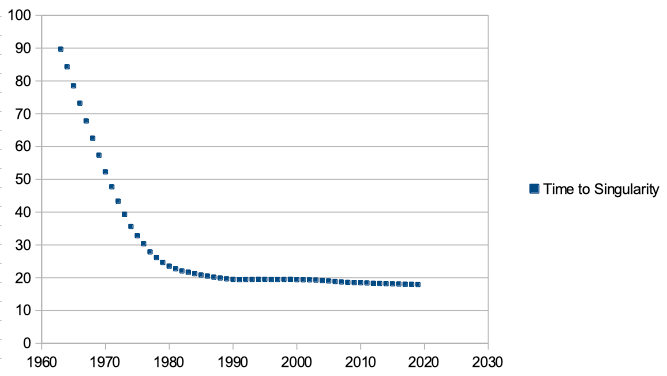

This graph shows the predicted number of years until the “singularity”—the moment when economic growth hits infinity—for every starting year from 1960 until today.

(Calculated using my fork of David Roodman’s GitHub repo.)

In 1960, a hyperbolic model predicted that the singularity was 90 years away. By about 1980, the singularity looked only 20 years away. But since 1980, this model has consistently predicted a singularity 20 years away from the present date.

Scott Alexander finds a similar result, although he claims that the singularity was “cancelled” in around 1960, not 1980. I couldn’t find his data source, so I’m not sure why he reports a different year. Either way, we both reach the same basic conclusion: that hyperbolic growth appears to have stopped.

In the comments of the Open Philanthropy blog post, Greg Colbourn makes the same observation: “the time to the singularity has remained ‘a few decades away’ over the last few decades.”1

I believe the recent non-hyperbolic behavior of economic growth casts significant doubt on whether a hyperbolic curve accurately describes future growth. But hyperbolic model still raises some interesting considerations:

- It’s remarkable that economic growth accelerated hyperbolically from 10,000 BC until 1960-1980.

- The growth rate might resume accelerating at some point in the future, perhaps due to the development of superintelligent AI (which Roodman mentions as a possibility).

- It looks like something important happened around 1960-1980 that caused hyperbolic growth to stop, and we might want to figure out what that was. Perhaps we hit some kind of upper limit on growth? What causes this limitation2?

Notes

-

Colbourn’s observation comes from data that David Roodman provided in the comments, at Colbourn’s request. Roodman’s regressions provide different results than mine, I’m not sure why. I calculated my regressions by taking the logarithms of the x and y values and then running a linear regression, which I believe is a reasonable way to fit a hyperbolic curve to data, but I don’t know much about statistics, so I could be doing something wrong. But we both find that the singularity has been perpetually N years away since 1980, for some fairly stable value of N. ↩

-

Scott Alexander theorizes that hyperbolic economic growth arises when growing population increases technological advancement, and technological advancement enables faster population growth. As a result of the demographic transition, populations have stabilized in developed countries, thus ending hyperbolic growth. David Roodman writes that finite natural resources might impose an upper limit on economic growth. ↩