Two Types of Scientific Misconceptions You Can Easily Disprove

Last updated 2023-03-22 to add another example.

There are two opposite types of scientific claims that are easy to prove wrong: claims that never could have been proven in the first place, and claims that directly contradict your perception.

Type 1: The unknowable misconception

A heuristic for identifying scientific misconceptions: If this were true, how would we know?

Example: “People swallow 8 spiders per year during sleep.” If you were a scientist and you wanted to know how often people swallow spiders, how would you figure it out? You’d have to do a sleep study for thousands of person-nights where you film people sleeping using a night vision camera that’s so high-quality that it can pick up something as small as a spider (which, as far as I know, doesn’t exist) and then pore over the tens of thousands of hours of footage by hand to look for spiders (because this factoid originated in a time when computer software wasn’t sophisticated enough to do it for you) and track the locations of the spiders and count how often they crawl into people’s mouths without coming back out. This is all theoretically possible but it would be insanely expensive and who would be crazy enough to do it?

Example: “The average man thinks about sex once every 7 seconds.” People can’t even introspect on their own thoughts on a continuous basis, how would scientists do it? This one seems simply impossible to prove, regardless of how big your budget is or how crazy you are.

Example: “Only 7% of communication is verbal, and 93% is nonverbal.” What does that even mean? How would a scientific study quantify all the information that two people transmit during a conversation and measure its informational complexity, and then conclude that 93% is nonverbal? You can kind of measure the information in words by compressing the text, but there’s no known way to accurately measure the information in nonverbal communication.

(This factoid does come from an actual study, but what the study actually showed1 was that, among a sample of 37 university psychology students doing two different simple communication tasks, when verbal and nonverbal cues conflicted, they preferred the nonverbal cue 93% of the time.)

Type 2: The perception-contradicting misconception

You can disprove some common misconceptions using only your direct perception.

Example: “Certain parts of the tongue can only detect certain tastes.” You can easily disprove this by placing food on different spots on your tongue.

Example: “You need two eyes to have depth perception.” Close one eye. Notice how you still have depth perception. Or look at a photograph, which was taken from a fixed perspective. Notice how you can still detect depth in the photograph.

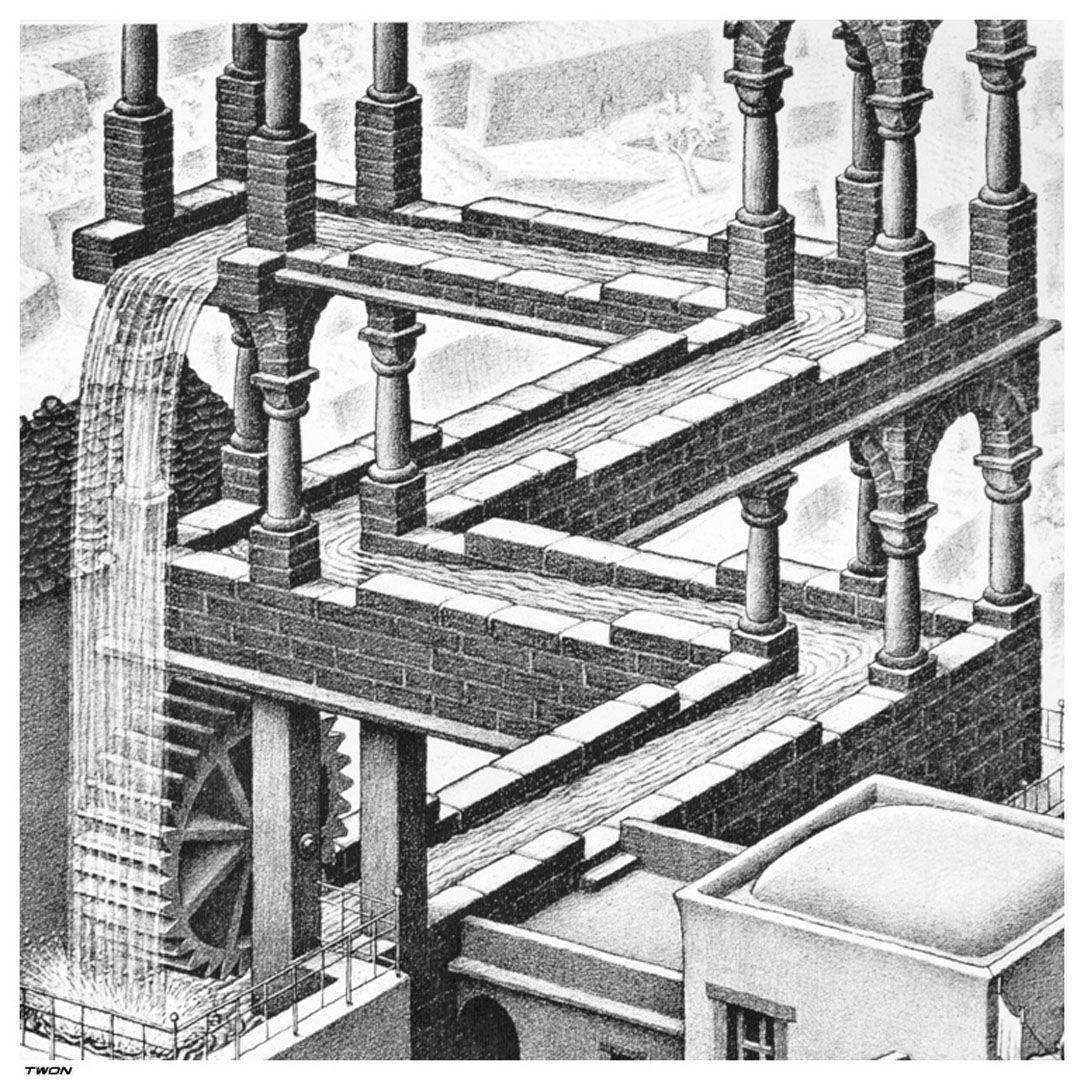

You need two points of reference to get “true” depth perception, but the human visual cortex can almost always infer depth based on how a scene looks. It’s possible to trick your depth perception, like this:

But in almost all real-world situations, you can correctly perceive depth with only one eye.

Example: “You (only) have five senses.” You can prove that you have at least two more senses: balance (equilibrioception) and the position of your limbs relative to each other (proprioception).

You can prove you have a sense of balance by closing your eyes and walking without falling over. You’re not using any of the standard five senses, but you can still stay upright.

You can prove you have proprioception by closing your eyes, flailing your arms around until they’re in random positions, and then bringing your hands together until your fingertips touch. You couldn’t do this if you didn’t have a proprioceptive sense.

(Some scientists say we have more than seven senses, but the other ones are harder to prove.)

So far I’ve given examples of factoids you can trivially disprove in five seconds. There are more misconceptions you can disprove if you’re willing to do a tiny bit of work. Example: “Women have one more rib than men.” Find a friend of the opposite gender and count your ribs!

-

Philip Yaffe (2011). The 7% Rule: Fact, Fiction, or Misunderstanding? ↩