Avoiding Caffeine Tolerance

Summary

Caffeine improves cognition1 and exercise performance2. But if you take caffeine every day, over time it becomes less effective.

What if instead of taking caffeine every day, you only take it intermittently—say, once every 3 days? How often can most people take caffeine without developing a tolerance?

The scientific literature on this question is sparse. Here’s what I found:

-

Experiments on rats found that rats who took caffeine every other day did not develop a tolerance. There are no experiments on humans. There are no experiments that use other intermittent dosing frequencies (such as once every 3 days).

-

Internet forum users report that they can take caffeine on average once every 3 days without developing a tolerance. But there’s a lot of variation between individuals.

This post will cover:

-

The motivation for intermittent dosing

-

A review of the experimental research on the effect of taking caffeine intermittently (TLDR: there’s almost no experimental research)

-

A review of self-reports from the online nootropics community

-

Intermittent dosing vs. taking caffeine every day

Epistemic status: I have never formally studied pharmacology or psychopharmacology—I’ve barely studied biology for that matter. But somehow nobody has ever looked into intermittent caffeine dosing to a degree that I found satisfactory3, so I did it myself.4

Updated 2024-03-08 to reference three more studies. h/t Gavin Leech for making me aware of them—see also his article on caffeine tolerance, which I think explains the concepts better than mine does.

- Summary

- Why intermittent dosing?

- Experimental evidence on intermittent dosing

- Individual self-reports

- Is intermittent dosing better than taking caffeine every day?

- Conclusion

- Appendix A: A study I would like to see

- Appendix B: Pre-registration for a caffeine self-experiment

- Notes

Why intermittent dosing?

The standard remedy for caffeine tolerance is to stop caffeine cold turkey for one to two weeks (or longer) to reset your body. Plenty of evidence suggests that this strategy works5, but I’m not happy with it.

The reason I’m not happy with it has to do with why I take caffeine: I want to improve cognition and exercise performance. If I stop having caffeine for two weeks, am I also supposed to take two weeks off work? Or spend two weeks being tired all day and getting nothing done? That sounds like a waste of time. Am I supposed to stop exercising for two weeks? That sounds unhealthy.

Taking caffeine intermittently makes more sense to me. If I take caffeine 3 times a week, that works a lot better:

- I can do the demanding high-effort work on caffeine days and do easier work on the non-caffeine days.

- I can do high-intensity exercise on caffeine days, and rest or do light cardio on the other days.

But I’d rather take caffeine 4–5 days a week if I can get away with it. And if I’ve unknowingly developed a tolerance, I’d rather scale back to once or twice a week. So I’d like to know the maximum frequency that doesn’t dampen caffeine’s benefits.

Experimental evidence on intermittent dosing

There are no studies on humans that administered caffeine less frequently than once a day. But there are a few studies on rats, which all found roughly the same result:6789

-

Rats who take caffeine every day develop a tolerance after 1–2 weeks.

-

Rats who take caffeine every other day do not develop a measurable tolerance after 2 weeks.

Some concerns with these studies:

-

They used rats, not humans. Humans are different in lots of ways, the most obvious being that we have slower metabolisms. A two-day abstinence for a rat might be the metabolic equivalent of a 6 to 10 day abstinence for a human. (Counterpoint: When taking caffeine daily, rats and humans develop tolerance at about the same rate.)

-

The studies only lasted 14 days. It’s possible that taking caffeine on alternating days still builds up a tolerance, but it takes longer than when taking caffeine daily (perhaps twice as long?).

-

Three of the four experiments were run by approximately the same research team, so any mistakes they made probably got repeated across all three of those experiments.

Individual self-reports

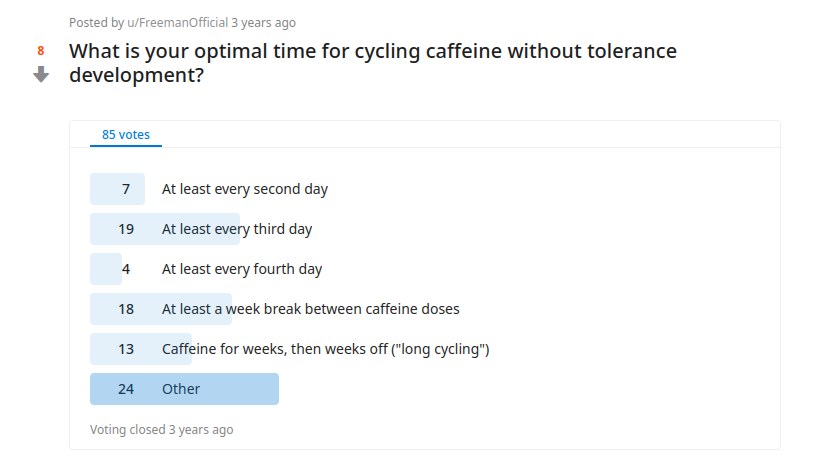

By far the best evidence I could find on how to avoid tolerance in humans was a 2021 reddit poll in the /r/caffeinecycling subreddit. An internet poll isn’t great evidence, but I’ll take what I can get.

(See footnote for the poll results in text format.10)

Among 84 respondents, at least 48 reported taking caffeine intermittently. 54% of those 48 reported that they do not develop a tolerance when taking caffeine every third day. And on average, they preferred to wait 3.58 days between doses.11

This suggests that:

-

On average, people can take caffeine every 3 days or so.

-

There’s a lot of variation between individuals, so you personally probably should take caffeine more or less often than that.

Some concerns with this poll:

-

This was based on self-reporting, not on any objective metric of performance.

-

It’s a biased sample: respondents found the poll because they were already interested in caffeine cycling. (I’d guess this poll over-represents people who develop caffeine tolerance quickly because people who don’t develop much tolerance won’t bother to cycle caffeine, and won’t go to a caffeine cycling subreddit.)

-

The rate of tolerance buildup depends on the size of the dose, but we don’t know anything about how much caffeine the poll respondents were taking.

I searched online nootropics forms (reddit.com/r/Nootropics/ and longecity.org) for anecdotes on commenters’ preferred caffeine frequency. The results broadly align with the /r/caffeinecycling poll; see footnote for a list of anecdotes.12

Is intermittent dosing better than taking caffeine every day?

If you take caffeine every day, you will develop a tolerance, but your performance might not fully revert to baseline. Could you get more benefit from taking caffeine daily than from cycling it? To answer that question, first we need to ask: How much ongoing benefit can you expect to get if you take caffeine daily?

Update 2024-03-29: I wrote a longer post about this question: Does Caffeine Stop Working?

Many studies have examined this question, but almost all of them are methodologically flawed to the point of being useless.13

I found exactly two studies (on humans) with strong methodology: Beaumont et al. (2017)14 and Lara et al. (2019)15. These studies gave participants either caffeine or placebo every day for 28 and 20 days (respectively) and tested their exercise performance before and after. The experiments both found that:

- Taking caffeine regularly decreased its potency, and this effect was statistically significant.

- Habituated users still retained 1/3 to 1/2 of the benefit of caffeine, but this effect was not statistically significant. (The studies could not rule out the possibility that habituated users saw zero positive effect from caffeine.)16

I found another few studies with decent but not great methodology: Rogers et al. (2013)17, Haskell et al. (2005)18, and Smith et al. (2006)19. These studies divided participants into caffeine non-users/low users versus high users. Then they randomly administered either caffeine or placebo and tested participants’ performance on various cognitive tests.

This methodology isn’t perfect because low and high users might differ in ways that could bias the results. (For more discussion of this possibility, see Rogers et al. (2013).) It would be better to randomize participants to take either caffeine or placebo for several weeks. Methodological limitations aside, these three studies suggest that high caffeine users do retain some benefits, although the exact amount varied depending on the study and the measurement used, from 28% to 315% (i.e., a habituated user experiences a 3x greater benefit than a naive user).20

Some studies on rats, cited previously6789, gave rats caffeine daily for 14 days and found that they retained somewhere between none and all of the performance benefits of caffeine, depending on the study. (Astute readers will notice that this doesn’t narrow things down much.)

***

Suppose caffeine retains 1/3 of its benefit when you take it every day—that’s my best guess given the available evidence. Compare that to taking caffeine only once every 3 days. Either way it’s about the same: either you’re getting 1/3 of the benefit every day, or the full benefit on 1 out of 3 days.

Except they’re not really the same because some days matter more than others. For example, if you exercise 4 days a week and you take caffeine on 2 of those days, then you’re only taking caffeine on 2/7 days of the week, but you’re getting half the exercise benefit, which is better. For that reason, I would prefer taking caffeine intermittently over taking it daily.

Conclusion

Prior to writing this article, I was taking caffeine 3 days a week, on Monday, Wednesday, and Friday. I wanted to know if I could take caffeine more often without developing a tolerance. My research tentatively suggests:

- My approach was reasonable and there’s not compelling evidence for taking caffeine more or less often than I do currently.

- If I do experiment with taking caffeine more frequently, there’s a good chance that I will develop a tolerance.

Appendix A: A study I would like to see

I would like to see a randomized controlled trial on the effectiveness of caffeine when taken intermittently. If I had a big enough budget, I would design the study like this:

- Break participants into at least three groups:

- A placebo-control group who takes a placebo every day.

- A caffeine-control group who takes caffeine every day. (This group shows what fully-habituated users look like.)

- One or more experimental groups that take caffeine intermittently. If we can get a big enough sample size, have separate groups for a variety of dosing frequencies.

- Following the methodology of Beaumont et al. (2017)14, pre-test every group on athletic performance and/or cognition both when taking caffeine and when taking a placebo.

- Administer caffeine or placebo for at least 28 days (longer is better).

- At the end of the experiment, administer caffeine to all participants and test them again.

The study would then look at the following outcomes:

- Measure the benefit of caffeine as the performance on the final caffeinated test minus the performance on the two pre-tests.

- If a particular group performs better on the final test than on the placebo pre-test, that means they did not develop complete caffeine tolerance.

- If a group performs worse on the final test than on the caffeine pre-test, that means they developed at least some tolerance.

- Measure the performance of each group relative to the placebo-control group and the caffeine-control group.

- If an experimental group outperforms the caffeine-control group on the final test, that means intermittent dosing has succeeded at reducing tolerance formation.

- Which group gets the greatest total benefit as measured by performance multiplied by dosing frequency?

If we wanted to make the study more complicated, we could follow the design of Lara et al. (2019) and test the participants frequently throughout the study. That would let us run a regression on the course of caffeine tolerance and also compare the performance of intermittent caffeine users on caffeine days vs. placebo days. Or we could divide up the groups by dosage, giving some people 1.5 mg/kg and others 3 mg/kg (or some other dosage).

If I were on a budget, I’d scale down the study to only two groups: a daily-caffeine group and an intermittent-caffeine group. With no placebo group, we don’t know how well the intermittent group performs relative to baseline, but we can compare their tolerance development relative to the caffeine group, which I believe is more important.

Appendix B: Pre-registration for a caffeine self-experiment

Updated 2024-03-29 to fix typos and improve wording.

I am going to conduct the following experiment on myself, in which I test whether taking caffeine intermittently decreases its effectiveness.

I will test my reaction time by taking the humanbenchmark.com test twice in a row. One test consists of 5 reaction events, so this will give a total of 10 reaction events, taking my reaction time at that moment as the average of the 10 reaction times. I will take the test using the same computer, monitor, and mouse so that latency is consistent.

I will measure the effect of caffeine using a reaction time test because (a) caffeine is known to improve reaction time, (b) reaction time is easy to test, (c) it’s unlikely to improve with practice so it makes for a good consistent test variable, and (d) it’s hard to placebo-effect myself into improving my reaction time (which is important because I can’t blind myself).

Phase 1. Calibration phase. Take a reaction time test twice a day (following the same schedule as described in phase 3 below). Continue for four weeks. Plot a regression of my reaction time across the four weeks. The purpose of the calibration phase is to ensure that my reaction time does not improve from practicing every day.

During this phase I will continue drinking coffee 3 times per week (as I have been doing), but I won’t measure my reaction time on caffeine vs. non-caffeine days because the only purpose of this phase is to check that my reaction time doesn’t improve with practice.

Phase 2. Abstinence phase. Abstain from caffeine for one week (9 days total, in between the last Friday of the calibration phase and the first Monday of the test phase). Test reaction time during this week. If I was habituated to caffeine in phase 1 then my reaction time should improve over the course of phase 2 as my tolerance wears off. Measure the slope of reaction times across days during the abstinence phase.

Phase 3. Test phase. Resume drinking coffee 3 days a week and continue for four weeks. Take a reaction time test twice a day, at (say) 8am and then 10am—the exact time doesn’t matter, but the first test is before having coffee and the second is after coffee. (Or on days when I don’t have coffee, take the test at times before and after I when would have had coffee.)

The primary variable of interest is the difference in reaction time on caffeine days before and after taking caffeine. I will also look at the difference in the 8am vs. 10am tests on non-caffeine days to ensure that reaction time doesn’t get better on the second test even without caffeine.

After phase 3 completes, I will measure the following outcomes:

- Slope of the difference in reaction time between pre-caffeine and post-caffeine tests on caffeine days. (A negative slope indicates diminishing effect of caffeine.)

- Slope of reaction time across post-caffeine tests. (A positive slope suggests caffeine tolerance. Remember that positive = longer reaction time = bad.)

- Slope of reaction time across pre-caffeine tests. (A positive slope suggests caffeine withdrawal symptoms.)

Check if the slopes are statistically significant. If the slopes for variables #2 and #3 are both ascending but only one is statistically significant, or they are jointly statistically significant but individually insignificant, that suggests that I did develop a tolerance but that the experiment was underpowered. If both slopes are insignificant, that suggests no tolerance (or that the experiment was underpowered). If slope #2 or #3 is descending and statistically significant, that suggests something weird is going on and my experiment is probably invalid.

If the slopes are all approximately zero, that means I can probably have more caffeine before I develop a tolerance. In that case, conduct phase 4.

Phase 4. High-caffeine test phase. Increase coffee intake to 4 days a week for four weeks. Observe the same variables as phase 3.

This experiment is not blinded and it’s probably underpowered, but it’s better than nothing.

Thank you to Ansh Shukla for reviewing a draft of this caffeine self-experiment.

Notes

-

Astrid Nehlig (2010). Is Caffeine a Cognitive Enhancer? ↩

-

Erica R Goldstein, Tim Ziegenfuss, Doug Kalman, Richard Kreider, Bill Campbell, Colin Wilborn, Lem Taylor, Darryn Willoughby, Jeff Stout, Sue Graves, Robert Wildman, John L Ivy, Marie Spano, Abbie E Smith & Jose Antonio (2010). International society of sports nutrition position stand: caffeine and performance. ↩

-

There are a few posts on nootropics forums, particularly reddit.com/r/caffeinecycling/, but they don’t go into much depth. There are no academic papers that discuss intermittent dosing in humans. ↩

-

I originally just wanted to answer the question for myself, but by the time I had read through about 10 studies and a bunch of forum posts, I figured I might as well write something up about it. ↩

-

Laura Juliano & Roland Griffiths (2004). A critical review of caffeine withdrawal: empirical validation of symptoms and signs, incidence, severity, and associated features. ↩

-

C. J. Meliska, R. E. Landrum & T. A. Landrum (1990). Tolerance and sensitization to chronic and subchronic oral caffeine: effects on wheelrunning in rats. ↩ ↩2

-

Omar Cauli, Annalisa Pinna, Valentina Valentini & Micaela Morelli (2003). Subchronic Caffeine Exposure Induces Sensitization to Caffeine and Cross-Sensitization to Amphetamine Ipsilateral Turning Behavior Independent from Dopamine Release. ↩ ↩2

-

N. Simola, E. Tronci, A. Pinna & M. Morelli (2006). Subchronic-intermittent caffeine amplifies the motor effects of amphetamine in rats. ↩ ↩2

-

Omar Cauli & Micaela Morelli (2002). Subchronic caffeine administration sensitizes rats to the motor-activating effects of dopamine D(1) and D(2) receptor agonists. ↩ ↩2

-

Poll results for “What is your optimal time for cycling caffeine without tolerance development?”

Votes Answer 7 At least every second day 19 At least every third day 4 At least every fourth day 18 At least a week break between caffeine doses 13 Caffeine for weeks, then weeks off (“long cycling”) 24 Other -

That’s with the assumption that all the “at least a week” respondents take caffeine exactly once a week. ↩

-

A list of anecdotes, paraphrased:

- christopherforums: I don’t develop tolerance when taking every 3–4 days, but do develop when taking every other day.

- /u/(deleted): 3 days a week is probably sustainable for 3–6 weeks before I’d want to take a week break. I can do once every 3 days indefinitely without building tolerance.

- /u/FreemanOfficial: I develop some tolerance when taking every second day, but no tolerance when taking every third day.

- /u/Lceus: For 3 months, I took caffeine for 3 days and then abstained for 4 days. The first caffeine days always had a strong effect, with the next 2 days having a positive but less enjoyable effect.

- /u/odd1e: I do 2x or 3x a week. If I do 3x for too long, a tolerance starts to build up.

- /u/owlthatissuperb: IME the best strategy is to drink coffee 2–3x per week.

- My own personal experience: I take caffeine either 3x or 3.5x a week (the extra 0.5x means I take a half-dose on one day). I don’t believe I’ve developed (much) tolerance because I don’t experience any withdrawal symptoms when I don’t take caffeine. I haven’t experimented with other dosing schedules, except that I used to drink coffee every day and I definitely developed a tolerance from that.

I also found anecdotes of people reporting that they intermittently take caffeine but without saying anything about why they do it that way, so I did not include those. ↩

-

Most randomized controlled trials on the benefits of caffeine cannot distinguish between two possibilities:

- Daily caffeine users get a persistent benefit from taking caffeine.

- Daily caffeine users who abstain from caffeine experience withdrawal symptoms, which hurts performance. Taking caffeine brings them back up to baseline performance, but they don’t do any better than they would have if they’d never developed a tolerance in the first place.

A literature review by James & Rogers (2005)21 discussed possible approaches for distinguishing these possibilities and looked at some studies that attempt these approaches. It concluded that the apparent benefits of caffeine are most likely due to reversing withdrawal symptoms. I believe this is an overly strong conclusion based on the studies they cited, and in fact the studies were simply too underpowered to show that caffeine has a positive effect for habituated users.

(The process of writing this article has significantly lowered my opinion of the field of psychopharmacology.) ↩

-

Ross Beaumont, Philip Cordery, Mark Funnell, Stephen Mears, Lewis Jamesa & Phillip Watson (2017). Chronic ingestion of a low dose of caffeine induces tolerance to the performance benefits of caffeine. ↩ ↩2

-

Beatriz Lara, Carlos Ruiz-Moreno, Juan Jose Salinero & Juan Del Coso (2019). Time course of tolerance to the performance benefits of caffeine. ↩

-

An explanation of how I drew conclusions from these two studies:

Lara et al. (2019) gave one group a placebo and the other group caffeine every day for 20 days and tested their exercise performance every few days using various metrics such as maximum power output and VO2 max The caffeine group consistently outperformed the placebo group, but the performance difference between the two groups declined by between 1/3 and 2/3 by day 20 (with different metrics of performance declining by different amounts). The authors did not report significance tests on the change in marginal benefit of caffeine between day 1 and day 20 but it was consistently negative across all metrics.

Beaumont et al. (2016) pre-tested participants’ performance both with caffeine and with placebo. Then participants took either caffeine or placebo for 28 days and took another test along with a dose of caffeine. In this experiment:

- The caffeine group performed significantly worse on the final test than on the pre-test with caffeine.

- The caffeine group performed non-significantly better on the final test than on the pre-test with placebo. This suggests that caffeine may have provided some benefit even with tolerance, but we can’t rule out the possibility that it had no benefit.

- The maximum-likelihood possibility is that caffeine tolerance reduces its benefits by 66%. (In the pre-test, the caffeine group did an average of 38.4 kJ more work with caffeine than with placebo. In the post-test, they did 13.1 kJ more work than in the placebo pre-test and 25.3 kJ less than in the caffeine pre-test. The observed reduction in marginal power output is 25.3 / 38.4 = 66%.)

Taken together, these experiments suggest that caffeine retains something like 1/3 of its benefit even after habituation.

However, we should not over-update on these results. Lara et al. had only 11 participants and Beaumont et al. had 18 participants. Given the small n and small effect sizes, we can’t draw strong conclusions from either of these two studies. And their methodologies might not generalize:

- They both gave participants 3 mg caffeine per kg bodyweight (which is around 200 mg for an average-sized person), so we don’t know what happens at other dosages. Some research suggests that users see best results at doses twice that high.

- The experiments lasted 20 and 28 days, respectively, so we don’t know if caffeine tolerance continues to build up over several months.

- The participants they recruited were not representative of the general population.

- They only looked at benefits to exercise performance, not cognition.

-

Peter Rogers, Susan Heatherley, Emma Mullings & Jessica Smith (2013). Faster but not smarter: effects of caffeine and caffeine withdrawal on alertness and performance. ↩

-

Crystal Haskell, David Kennedy, Keith Wesnes & Andrew Scholey (2005). Cognitive and mood improvements of caffeine in habitual consumers and habitual non-consumers of caffeine. ↩

-

Andrew Smith, Gary Christopher & David Sutherland (2006). Effects of caffeine in overnight-withdrawn consumers and non-consumers. ↩

-

None of these studies directly reported the information we care about, but I was able to figure some things out from what they did report.

We want to know the benefit of caffeine for a habitual user. We can measure that by comparing the performance of high-caffeine users after taking caffeine versus low-caffeine users after taking placebo. If high users develop a complete caffeine tolerance then these two groups should perform the same—when a habitual user takes caffeine, it’s as if they’ve taken nothing.

If we want to know exactly how much of the benefit habitual users retain, it gets a little bit complicated, but we can still figure it out. Start by deriving two variables from the groups’ performance:

- baseline benefit of caffeine for naive users = low-caffeine users on caffeine – low-caffeine users on placebo

- absolute retention of benefits for habituated users = high-caffeine users on caffeine – low-caffeine users on placebo

Then calculate relative retention as benefit / retention.

I performed this calculation using the primary performance metrics from each study (ignoring self-reported metrics like sleepiness) and got the following results.

Rogers et al. (2013) had by far the biggest sample size at 369 (compared to 48 and 25 for Haskell et al. and Smith et al., respectively). Rogers et al. did not report means or standard errors for the individual experimental groups, but it did report (ANOVA) significance tests for the four main performance metrics used by the study22. I can summarize the results as:

- Across all four metrics, high-caffeine users performed worse than low-caffeine users when given placebo, and 3/4 differences were statistically significant.

- High-caffeine users on caffeine outperformed low-caffeine users on placebo on 3/4 metrics. 2 out of those 3 were statistically significant.

- High-caffeine users on caffeine actually outperformed low-caffeine users on caffeine on (a different set of) 2 metrics (but these results were not significant).

- From eyeballing the graphs in the paper, the four metrics had relative retentions of approximately 120%, 140%, –30%, and 80%, with the second and fourth retentions being significantly different from 0.

These results suggest that:

- Habitual users experience withdrawal symptoms when they stop taking caffeine.

- Habitual users still retain some benefit above baseline—they do not become fully habituated to caffeine.

- Possibly, habitual users do not lose any of the benefits. (The results lean this way, but not strongly.)

The other two studies did report means, so I can explicitly quantify the relative rentention of the benefits of caffeine. In the tables below, I report the retention, benefit, and relative retention for the main metrics the studies used.

From Haskell et al. (2005): (RT = reaction time, RVIP = rapid visual information processing)

Metric Retention Benefit Retention % simple RT -17.64 -5.6 315% digit vigilance RT -15.5 -16.2 96% RVIP false alarms -0.5 -0.21 238% spatial memory 0.01 0.01 100% numeric memory RT -11.92 -42.42 28% From Smith et al. (2006):

Metric Retention Benefit Retention % focused attention speed -4.2 -8.6 49% categoric search RT -5.5 -16.4 34% simple RT -38.1 -41.4 92% repeated digits vigilance 2.13 3.32 64% (Both studies reported a lot more metrics, but they highlighted these as the most important.)

For the Haskell et al. data, on each of the five metrics, the difference between retention and benefit was not statistically significant at p=0.05, and the absolute retention was not significantly different from zero (digit vigilance RT came close with p = 0.054).

I can’t do significance tests on the Smith et al. data because the paper didn’t report standard errors. But given that it had a smaller sample size than Haskell, I’d guess none of the differences are statistically significant.

I wanted to do some Bayesian statistics where I’d calculate a posterior distribution over relative retention based on every individual metric from the three studies. But I realized it would be kind of pointless because Rogers et al. (2013) doesn’t report p-values (only significance / insignificance), so I can’t do odds updates for the study that should provide by far the biggest odds updates. ↩

-

Jack E. James & Peter J. Rogers (2005). Effects of caffeine on performance and mood: withdrawal reversal is the most plausible explanation. ↩

-

Rogers et al. (2013) tested 8 metrics, including 3 self-reported metrics and 5 performance tests. I ignored one of the performance tests because the low-caffeine placebo group outperformed the low-caffeine caffeine group, which means the concept of “retention” is not well-defined. (There is no benefit to retain if caffeine has a negative effect.) ↩