Subjects in Pysch Studies Are More Rational Than Psychologists

Psychologists have done experiments that supposedly show how people behave irrationally. But in some of those experiments, people do behave rationally, and it’s the psychologists’ expectations that are irrational.

Contents

- Contents

- Ultimatum game

- Hyperbolic discounting

- Dunning-Kruger effect

- Non-examples: Asch and Milgram

- Themes

- Notes

Ultimatum game

The ultimatum game works like this:

There are two participants, call them Alice and Bob. Alice receives $100. Alice then chooses some amount of that money to offer to Bob. Bob can accept the offer and they both walk away with their money, or he can reject the offer in which case they both get nothing.

According to standard theory, Alice should offer Bob $1 and keep $99 for herself, and Bob should accept the offer because a dollar is better than no dollars. In practice, most “Alices” offer something like a 50/50 split, and most “Bobs” reject the offer if given something like an uneven split. Psychologists1 are confused about this supposedly irrational behavior.

But in fact, Alice and Bob both behave rationally. Bob rejects unfair offers, which makes him have less money in some cases. But Alice expects Bob to reject unfair offers, so she offers Bob a 50/50 split.

Bob follows a general strategy of rejecting unfair offers, because he believes or intuits that this strategy will ensure he mostly receives fair offers. And Alice knows Bob will probably reject an unfair offer because that’s what most people do. So Bob has (acausally) induced Alice to give him $50 instead of $1. In the world where Bob rejects unfair offers, Bob wins.

In other words, most people don’t use causal decision theory.

Hyperbolic discounting

The standard model of rational behavior assumes exponential discounting: future goods decrease in value at a fixed rate (say, 10% per year). But experiments show that many people use hyperbolic discounting, which means the value of future goods first falls off rapidly, and then slowly.

The classic experiment:

- Ask people if they would prefer $100 now or $120 a month from now. Most people prefer the $100 now.

- Ask people if they would prefer $100 in 12 months or $120 in 13 months. Most people prefer the $120 in 13 months.

Psychology textbooks say this is irrational: the monthly discount rate must be either more than 20% (in which case they should take the money sooner in both cases) or less than 20% (in which case they should take the money later). But in real life, people’s behavior makes sense.

If you say you’re going to give me money right now, you’re probably going to do it. If you say you’re going to give me $120 a month from now, I don’t know what’s going to happen. Maybe you’ll forget, maybe your study will run out of funding, I don’t know. So I’d rather have the money now.

If you can give me money in 12 months, you can most likely also give me money in 13 months, so I’m not too concerned about waiting an extra month in that case.

In mathematical terms, the probability that you’ll give me the money decreases hyperbolically with time, not exponentially, so I ought to use hyperbolic discounting.

(Plus there is another, more technical, reason to use hyperbolic discounting: if the “true” discount function is exponential but you don’t know what exact discount rate to use, then your expected discount rate starts out high and decreases over time, which produces a hyperbolic discount function.)

Dunning-Kruger effect

The Dunning-Kruger effect is often misrepresented as showing that ignorant people think they’re knowledgeable, and knowledgeable people think they’re ignorant. To my knowledge, no study has ever showed that.

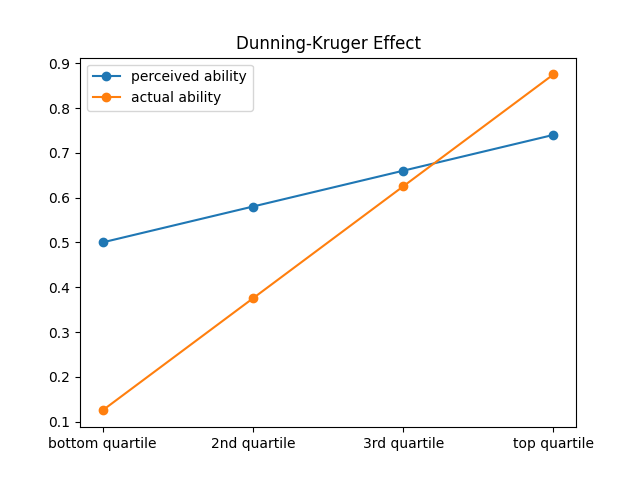

The original Kruger & Dunning (1999)2 paper, and some follow-up studies, produced graphs that looked something like this:

(This graph is an illustration, not based on actual data.)

Notice two things about this graph:

- The “perceived ability” line is a bit too high.

- The slope is too flat—everyone estimates their ability as closer to average than it really is.

#1 is a real (albeit small) bias—people systematically overestimate their abilities by a little bit. But the flattened slope of perceived ability is rational, for two reasons.

Reason 1. If your test has some degree of noise, then you expect the top scorers to have gotten lucky and the bottom scorers to have gotten unlucky. The top scorers aren’t quite as good as the test makes them look, and the bottom scorers aren’t quite as bad as the test makes them look. So the true skill curve is flatter than the measured skill curve. For more on this, see Gignac & Zajenkowski (2020)3.

Reason 2. People do not have perfect knowledge of their own abilities. If you know nothing else, you should expect to perform about average. If you know a little bit about your own skill level, you should expect to perform a little below or a little above average. Even if you’re in the top 10% or bottom 10% of skill, it should take a lot of evidence to convince you of that, so it’s perfectly rational for you to estimate your own skill as closer to average than it really is.

Both these reasons say essentially the same thing: if you have a noisy measure of ability, your belief conditional on that measure should be closer to average than what the measure itself shows. This produces a flattened curve like what we see in the Dunning-Kruger effect, and it’s not a bias but a perfectly rational way of reasoning about imperfect evidence.

Non-examples: Asch and Milgram

Originally I wanted to include the Asch conformity experiments and the Milgram experiments on this list—I thought participants behaved rationally. But after doing some more research, I think the rational-participant theory can’t fully explain the observations.

(If you’re not familiar with the Asch or Milgram experiments, click the links in the previous paragraph for explanations. They’re a bit too complicated to explain in this post.)

For Asch, I originally wanted to argue that it’s rational to update your beliefs when other people disagree with you. But the experiments found that people are more willing to disagree with the group when they can give their answers in secret. If people were rationally updating on others’ beliefs, then they’d agree with the group in secret as well as in public.

I still think it’s rational for subjects to update their beliefs toward those of the other participants, but the experiments suggest that people update more than they should.

For Milgram, I wanted to argue that participants who continue to administer electric shocks have rationally (and correctly!) deduced that nothing bad is happening. This is consistent with people’s behaviors, but it’s not consistent with their stated beliefs (almost all participants report believing that it was real) or their observed emotional state (many of them were visibly sweating/trembling/having nervous fits).

Themes

What can we learn from how psychologists mis-interpret these experiments?

- People consider more types of evidence than pychologists think they do.

- People intuitively use non-causal decision theories.

Notes

-

Or at least psychology textbooks, it’s possible that many actual psychologists are smarter about this. ↩

-

Kruger, J., & Dunning, D. (1999). Unskilled and unaware of it: how difficulties in recognizing one’s own incompetence lead to inflated self-assessments. ↩

-

Gignac, G. E., & Zajenkowski, M. (2020). The Dunning-Kruger effect is (mostly) a statistical artefact: Valid approaches to testing the hypothesis with individual differences data. ↩