Do Small Protests Work?

TLDR: The available evidence is weak. It looks like small protests may be effective at garnering support among the general public. Policy-makers appear to be more sensitive to protest size, and it’s not clear whether small protests have a positive or negative effect on their perception.

Previously, I reviewed evidence from natural experiments and concluded that protests work (credence: 90%).

My biggest outstanding concern is that all the protests I reviewed were nationwide, whereas the causes I care most about (AI safety, animal welfare) can only put together small protests. Based on the evidence, I’m pretty confident that large protests work. But what about small ones?

I can see arguments in both directions.

On the one hand, people are scope insensitive. I’m pretty sure that a 20,000-person protest is much less than twice as impactful as a 10,000-person protest. And this principle may extend down to protests that only include 10–20 people.

On the other hand, a large protest and a small protest may send different messages. People might see a small protest and think, “Why aren’t there more people here? This cause must not be very important.” So even if large protests work, it’s conceivable that small protests could backfire.

What does the scientific literature say about which of those ideas is correct?

Contents

- Contents

- Evidence from nationwide natural experiments

- Direct evidence from lab experiments

- Indirect evidence from lab experiments

- Non-experimental evidence

- Conclusion

- Future work

- Appendix: Table of papers from Orazani et al. (2021)

- Notes

Evidence from nationwide natural experiments

Among the studies in my prior lit review, two studies modeled how voter outcomes varied based on the number of protesters in each county. The two studies found that each marginal protester increased vote share by 18.81 and 9.62 respectively (where vote share = number of votes adjusted to account for voter turnout1).

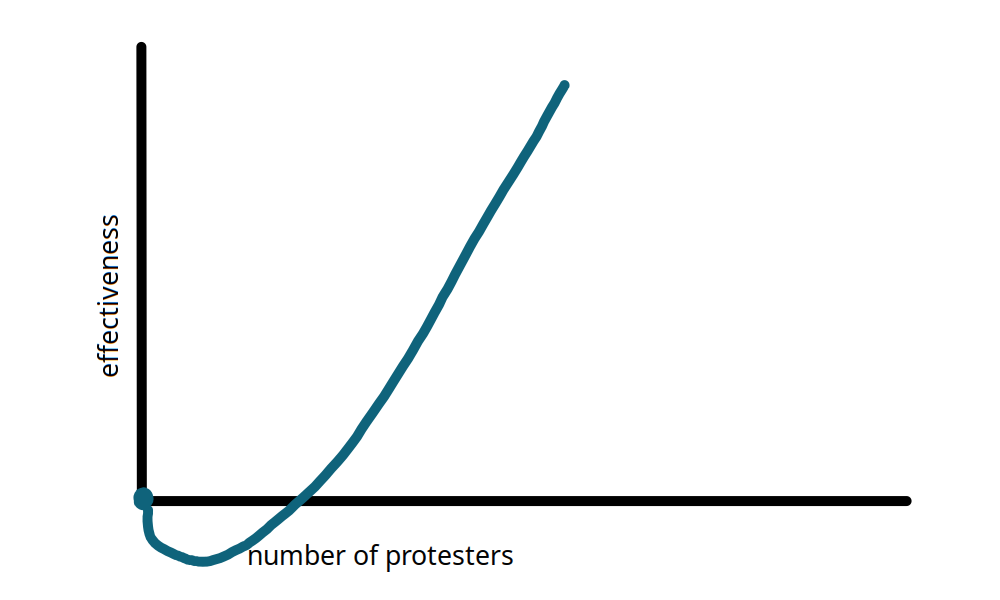

Unfortunately, these studies both used linear models, which doesn’t help us. We want to know if there’s a non-linearity near zero—something that looks like this:

A linear model can’t tell you what the shape of the curve looks like, or whether it dips into the negative for sufficiently small protests.

(In theory, I could analyze the raw data myself, but that would be a lot of work.)

Direct evidence from lab experiments

To my knowledge, there are two experiments that directly tested whether the size of a protest affected people’s support for a cause.

Wouters & Walgrave (2017)2 showed (fictitious) news articles to Belgian legislators. The news articles said either “There were about 500 participants which was much less than expected”, or “There were more than 5,000 participants which was more than expected.”3 The authors also altered three other independent variables, which they called Worthiness, Unity, and Commitment. Then they asked participants questions to judge how much they agreed with protesters (“position”) and whether they intended to take any actions to support protesters (“action”). Below I present the resulting regression coefficients and p-values.

| position | p-val | action | p-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers | 0.282 | 0.008 | 0.439 | 0.000 |

| worthiness | 0.381 | 0.000 | 0.116 | 0.297 |

| unity | 0.353 | 0.001 | 0.350 | 0.002 |

| commitment | 0.190 | 0.300 | 0.156 | 0.161 |

Numbers had biggest or near-biggest p-values out of the four variables, which suggests that legislators care a lot about the size of a protest. However, this study did not include a control group, so we don’t know whether smaller protests had a positive effect, a negative effect, or no effect.

Wouters (2019)4 conducted two similar studies, this time interviewing members of the general public rather than legislators. They described protest sizes the same way as Wouters & Walgrave (2017) (“500, less than expected” vs. “5,000, more than expected”), and again used four independent variables. Below are the regression coefficients and p-values from the two different studies, where the dependent variable was participants’ support for the cause.

| study 1 | p-val | study 2 | p-val | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| numbers | 0.094 | 0.071 | 0.063 | 0.291 |

| diversity | 0.168 | 0.001 | 0.131 | 0.029 |

| worthiness | 0.607 | 0.000 | 1.127 | 0.000 |

| unity | 0.201 | 0.000 | 0.126 | 0.034 |

In this case, we find that numbers matter less than the other three factors.

Taken together, these two papers suggest:

- Legislators care a lot about protest size. The general public maybe cares a bit, but not much.

- Even (comparatively) small protests are effective at garnering support from the general public. It’s not clear whether they are effective for legislators.

(If small protests turned off the general public, then we would see that the “numbers” variable has good predictive power, but it doesn’t.)

Indirect evidence from lab experiments

Wouters & Walgrave (2017)2 and Wouters (2019)4 were the only two papers I could find that directly tested the effect of protest size. But there could also be indirect evidence. I’m imagining something like this:

- A lab experiment showed people either a new article about a protest, or a “control” news article. People who read about the protest were [more/less] supportive of the protesters’ cause.

- The protest described in the article happened to be small.

That result would provide evidence about how small protests influence people.

To see if there was something like that, I looked through the studies cited by a meta-analysis by Orazani et al. (2021)5. I found two relevant papers: Thomas & Louis (2013)6 and Feinberg et al. (2017)7. (See Appendix for a list of every paper.)

Thomas & Louis (2013)6 did two experiments comparing participants’ reactions to news articles about violent vs. nonviolent protests. The two experiments were more or less the same, except that Experiment 1 covered fracking protests and Experiment 2 was about anti-whaling activism. Unfortunately the contents of the news articles are not publicly available and the corresponding author did not reply to my inquiry, so I don’t know how the protests were described in terms of size.

Feinberg et al. (2017)7 included three studies. Each study presented participants with an article or video about a different protest.

- Study 1: The articles described a fictitious animal rights group. Protest size was reported in the articles as “about thirty people”.

- Study 2: The articles described a Black Lives Matter march. The number of protesters was not specified in the articles.

- Study 3: Participants were shown videos of Trump protests. One video showed a protest with roughly 70 participants8 but I don’t know how many protesters were in the other video.

In study 1, study participants reported relatively high support for protesters in the “Moderate” condition, in which a fictional animal rights group picketed a cosmetics company. (In the “Extreme” condition, the protesters broke into the building and freed animals.) However, there was no control group (!!), so we don’t know if reading about the protest caused support to go up, or if support would’ve been high anyway. The protest was described as having only thirty people, so this would’ve been useful evidence if they’d included a control group, but they didn’t.

One thing we can say about study 1 is that if small protests reduce support, then they don’t reduce support by as much as “extreme” protests do.

There is one additional paper, Bugden (2020)9, that was not included in the Orazani et al. meta-analysis.10 It showed participants articles in four conditions: a control,11 peaceful protest, disruptive protest, and violent protest. The peaceful protest article (found in the supplement document) opened with:

On Thursday, thousands of protestors took to the streets as the state legislature prepares to vote on a climate change bill.

This protest was not small, so Bugden (2020) doesn’t provide relevant evidence.

Non-experimental evidence

An observational study by Ostarek et al. (2024)12 studied the effect of a disruptive protest by the climate group Just Stop Oil in which protesters blockaded a highway. By running polls before and after, the researchers found that support for a more moderate climate group, Friends of the Earth, increased just after the Just Stop Oil protest.

The protest consisted of 45 people (source).

At first glance, this appears to indicate that small protests can be effective. But I’m not sure that’s an appropriate interpretation of the evidence, because:

- It was an observational study, not an experiment or even a natural experiment.13

- Other studies have found negative effects for disruptive protests.

Conclusion

None of the evidence I found was very good.

Here are my takeaways, but given the state of the evidence, I don’t have much confidence in them.

- Large protests work better than small protests at garnering support among policy-makers. (credence: 80%)

- The general public probably doesn’t greatly care about the size of a protest. (credence: 60%)

- Small protests can probably be effective at garnering support among the general public. (credence: 60%)

Do small protests persuade the general public? Looks like yes (but, at the risk of repeating myself, the evidence was not strong).

Do small protests persuade policy-makers? I couldn’t find any evidence either way. (But the fact that I couldn’t find anything is weak evidence against.)

Future work

I see two obvious ways to learn more about how well small protests work. They’re out of scope for this post, but they wouldn’t be too hard.

- Analyze the data collected in natural experiments and use a non-linear model to assess the effectiveness of small protests.

- Run a new survey (on Mechanical Turk or similar) showing people small protests vs. large protests. vs. no protests and then ask them about their opinions on the protesters’ cause.

Appendix: Table of papers from Orazani et al. (2021)

| Paper | Status |

|---|---|

| Thomas & Louis (2014) | included useful information |

| Orazani & Leidner (2018) | I couldn’t find the full text |

| Becker et al. (2011) | dependent variable was not relevant |

| Feinberg et al. (2017) | included useful information |

| Gutting (2017) | dependent variable was not relevant |

| Leggett (2010) | unpublished |

| Shuman et al. | unpublished |

Notes

-

Mathematically, vote share per protester equals raw votes per protester divided by the proportion of residents who voted. ↩

-

Wouters, R., & Walgrave, S. (2017). Demonstrating Power. ↩ ↩2

-

I suspect that the phrases “less/more than expected” have a bigger effect on people’s perception than the numbers themselves. But this hypothesis hasn’t been tested. Some evidence for my hypothesis is that Madestam et al. (2013)14 (which I reviewed previously) found a strong county-level effect on protests, and the average protest size was 815 people per county, which is much closer to the “small” condition (500 people) than the “large” condition (5,000). So my guess is that 500 only sounds small because the article presented it as “less than expected”. However, the protests studied in Madestam et al. (2013) might differ in other meaningful ways. ↩

-

Wouters, R. (2019). The Persuasive Power of Protest. How Protest wins Public Support. ↩ ↩2

-

Orazani, N., Tabri, N., Wohl, M. J. A., & Leidner, B. (2021). Social movement strategy (nonviolent vs. violent) and the garnering of third‐party support: A meta‐analysis. doi: 10.1002/ejsp.2722 ↩

-

Thomas, E. F., & Louis, W. R. (2013). When Will Collective Action Be Effective? Violent and Non-Violent Protests Differentially Influence Perceptions of Legitimacy and Efficacy Among Sympathizers. ↩ ↩2

-

Feinberg, M., Willer, R., & Kovacheff, C. (2017). Extreme Protest Tactics Reduce Popular Support for Social Movements. ↩ ↩2

-

Source: I watched the video and counted how many people I could see. Some of the people were clearly bystanders, not protesters, but others were ambiguous so I’m not sure about the exact count. ↩

-

Bugden, D. (2020). Does Climate Protest Work? Partisanship, Protest, and Sentiment Pools. ↩

-

Even though Orazani et al. was published in 2021, its literature review was conducted in 2018. ↩

-

The control condition simply noted that protests exist without describing them at all, and asked participants if they supported the protesters’ cause. ↩

-

Ostarek, M., Simpson, B., Rogers, C., & Ozden, J. (2024). Radical climate protests linked to increases in public support for moderate organizations.

See also a less-technical 2022 preprint at https://www.socialchangelab.org/_files/ugd/503ba4_a184ae5bbce24c228d07eda25566dc13.pdf. ↩

-

I don’t see how the change wouldn’t be causal, but that could just be a failure of imagination on my part. ↩

-

Madestam, A., Shoag, D., Veuger, S., & Yanagizawa-Drott, D. (2013). Do Political Protests Matter? Evidence from the Tea Party Movement*. ↩