Writing Your Representatives: A Cost-Effective and Neglected Intervention

Is it a good use of time to call or write your representatives to advocate for issues you care about? I did some research, and my current (weakly-to-moderately-held) belief is that messaging campaigns are very cost-effective.

In this post:

- I look at evidence from randomized experiments, surveys of legislators’ opinions, and observational evidence. All lines of evidence suggest that messaging campaigns are effective, but none of the evidence is strong.

- I write an estimate of how many messages it takes to get a bill to pass in expectation, and how much that costs. According to my model, changing a vote outcome takes 17,000 messages for the Michigan state legislature and 2.2 million messages for US Congress.

- I provide links to resources on how to participate in messaging campaigns for animal welfare, AI safety, and global poverty.

Cross-posted to the Effective Altruism Forum.

Contents

- Contents

- Evidence from randomized experiments

- Evidence from surveys

- Observational evidence

- Theoretical argument

- State vs. federal representatives

- Cost-effectiveness estimate

- So, are messaging campaigns cost-effective?

- How to participate in messaging campaigns

- Notes

Evidence from randomized experiments

There are two randomized controlled trials on messaging campaigns targeted at legislators: Bergan (2009)1 and Bergan & Cole (2014)2. These studies randomly assigned state legislators to either receive or not receive messages from volunteers advocating in favor of an upcoming bill, and then looked at how many legislators voted for the bill depending on whether they received messages or not.

Both studies found statistically significant differences. Bergan (2009) found that the messaging campaign increased positive votes by 20 percentage points, and Bergan & Cole (2014) found a 12 percentage point improvement.

This table summarizes key facts about the studies:

| State | Medium | Avg # Messages | Change | |

|---|---|---|---|---|

| Bergan (2009) | New Hampshire | 3 | 20%pp | |

| Bergan & Cole (2014) | Michigan | phone | 22 | 12%pp |

Bergan & Cole (2014) had legislators in the experimental group receive either 22, 33, or 65 calls. The study was underpowered to detect differences between those numbers, but the 65-calls group showed a (non-significantly) weaker effect than 22 or 33, which hints that the number of calls doesn’t matter beyond a certain point.

Evidence from surveys

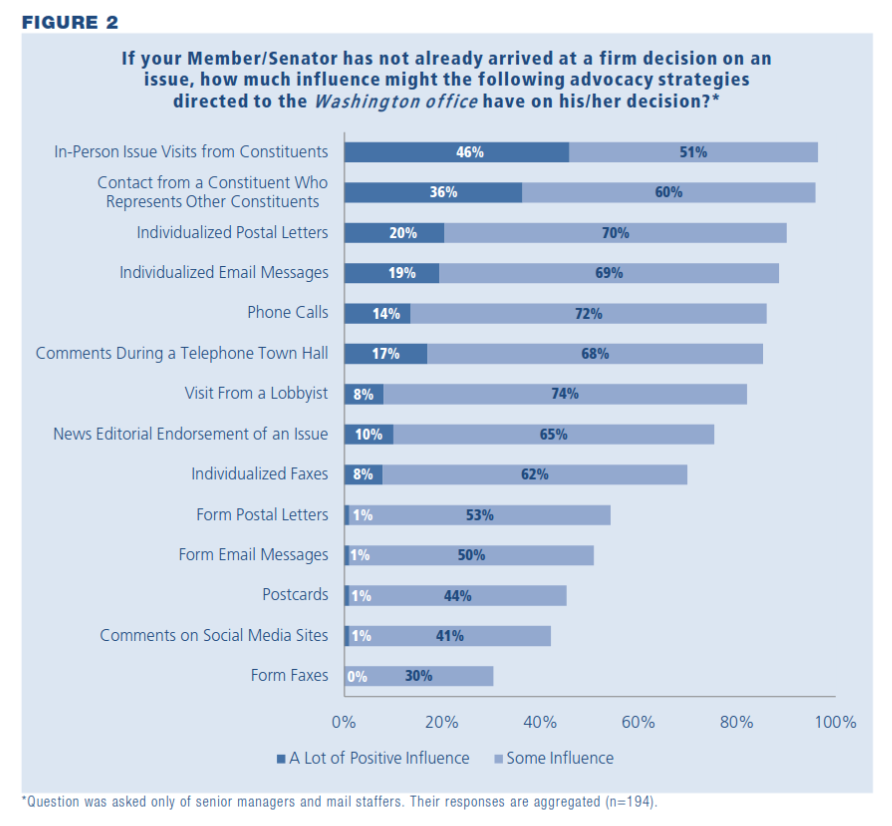

A survey3 by the Congressional Management Foundation asked US Congress senior staffers how much weight they give to different forms of communication:

Respondents overwhelmingly say they give influence to constituents, although I’m not sure how seriously to take this because there’s a strong social desirability bias at play.

But insofar as we can take these results seriously:

- In-person visits are better than individualized messages.

- Individualized messages from constituents are more influential than lobbyists. (I am somewhat skeptical of this.)

- Lobbyists are more influential than form messages.

- Most respondents still give “some influence” to form messages.

- There isn’t much difference between postal letters, email, and phone calls, although phone calls were the worst of the three. (This is good news for me as someone who’s allergic to making phone calls.)

An article from the OpenGov Foundation has a more qualitative perspective, with quotes from legislators about what kinds of advocacy they care most about.

When I’ve talked to lobbyists, they told me that policy-makers pay more attention to them than to constituents. These surveys by academics/think tanks say the opposite. Both of these pieces of evidence are contaminated by the fact that policy-makers are going to tell people what they want to hear. So ultimately you have to just decide who you believe more.

Observational evidence

One way to look at the question is to measure how well politicians’ votes align with public opinion vs. interest groups. That tells us something about how much politicians pay attention to the public compared to lobbyists, although this isn’t great evidence because politicians might vote one way or another for many reasons. And whether politicians align with public opinion doesn’t necessarily tell us how well messaging campaigns work, because there aren’t messaging campaigns on every issue.

And, the question is muddied by the fact that there can be interest groups on both sides of an issue, and possibly even public messaging campaigns on both sides.

As with most fields in social science, observational evidence is much easier to find than experimental evidence, so there are many research papers on this question. And because observational evidence is weaker than experimental evidence, I spent less time on it.

A systematic review by Elkjær & Klitgaard (2021)4 found very different answers across studies. Some studies found that public opinion mattered a great deal; others found that public opinion mattered far less than elite opinion or interest groups. Answers varied depending on how each study approached the problem and what statistical model they used.

I haven’t dug enough into the research to say whether some studies’ methodologies are better than others—it may be that some methodologies don’t make sense, and once you eliminate those, there is a single clear answer. But based on my cursory review, it looks to me like the observational evidence is mixed.

Theoretical argument

There is a simple theoretical reason to expect messaging campaigns to work well:

- A representative’s job is to do what their constituents want.

- If you tell them what you want, that increases the chances that they’ll do it.

And an argument for cost-effectiveness: most people don’t talk to their representatives, so if you do, you can have a big impact.

State vs. federal representatives

I’m only going to talk about the United States because I don’t know much about other governments. But my guess is that messaging campaigns should work roughly as well in any representative democracy as they do in America.

The two randomized experiments looked at vote outcomes from state representatives in a medium-sized state (Michigan) and a small state (New Hampshire). Federal representatives are representing many more people and therefore get more mail.

How much more mail? I don’t know. I couldn’t find data on the volume of mail received by state representatives. The fact that double-digit percentages of representatives changed their votes after receiving 22 phone calls (in Michigan) or three (!) emails (in New Hampshire5) suggests that they don’t receive many messages.

(Michigan has a population of 10 million and New Hampshire has 1.4 million, which is roughly consistent with the 7x difference in the number of messages sent for the respective advocacy campaigns.)

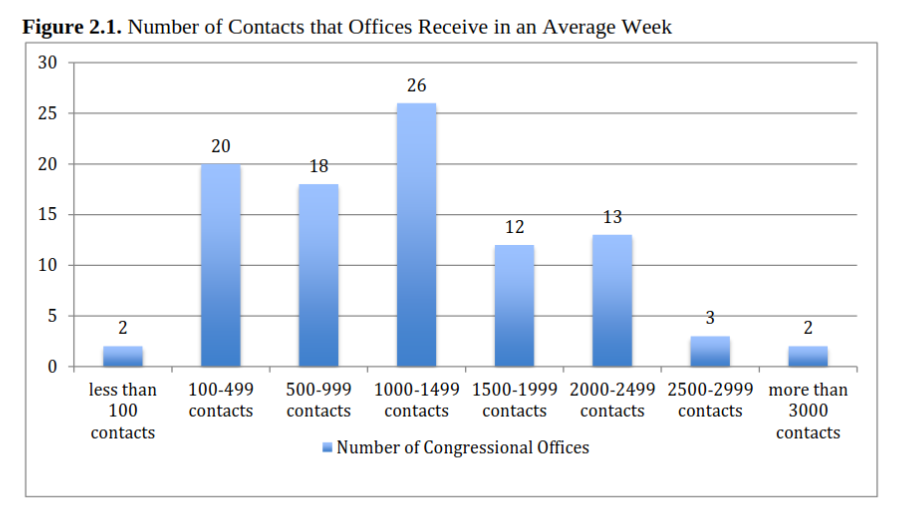

US Congress members, on the other hand, typically received 1000–1500 contacts per week in 2013 (Abernathy (2015)6):

They receive perhaps 3000 contacts per week today, although I couldn’t find a primary source.7

Cost-effectiveness estimate

I created a Squiggle model to estimate the cost-effectiveness of state and federal messaging campaigns. The model itself has documentation explaining how it works. I won’t explain every detail in this post—you can click through to the model if you’re interested—but I’ll give an overview of how it works.

- Bergan (2009)1 and Bergan & Cole (2014)2 randomly assigned state legislators to receive messages. They found vote shifts of 20 and 12 percentage points, respectively. My model uses smaller numbers to be conservative.

- Using data pulled from Congressional records, I estimated what proportion of vote outcomes could be flipped by shifting votes by N percentage points.

- Calculate

[percentage vote change per message] * [number of legislators] * [probability of outcome change for every 1% vote change]to get the expected probability of changing a vote outcome per message sent.

That’s just an outline. My model includes a lot of assumptions, and you probably disagree with some of them; if you’re opinionated, you should open the model and change the numbers as you see fit.

Then to get the cost to change a federal vote outcome, I scaled up based on the population difference between a medium-sized state and the United States as a whole. I added a 2x multiplier to adjust for the fact that US Congress is more salient and probably gets more messages per capita than state legislatures (as well as more advocacy via other vectors).

Multiplying all these factors together, my model came up with these results:

- Changing an outcome in the Michigan state legislature (taken as a representative medium-sized state) requires a median of 17,000 messages (mean 15,0008; 90% credence interval 6200 to 130,000).9

- Changing an outcome in US Congress requires a median of 2.2 million messages (mean 1.9 million; 90% credence interval 810,000 to 17 million).

Of course, that doesn’t mean you can brute-force your way into changing an outcome by running a giant multi-million-person messaging campaign. The model only applies to normal-sized campaigns. If you send, say, 19,000 messages, then—according to this model—you have a 1% chance of changing the outcome of a vote in Congress.

We can also calculate cost-effectiveness by assigning a monetary value to the time spent calling or writing letters. When I plugged in some best-guess numbers, I came up with:

- The median cost to change an outcome in the Michigan state legislature is $440,000 (mean $130,000; 90% credence interval $31,000 to $3.8 million).

- The median cost to change an outcome in US Congress is $58 million (mean $17 million; 90% credence interval $4 million to $500 million).

- The median cost to change an outcome in California (the largest US state) is $3.1 million (mean $930,000; 90% credence interval $220,000 to $27 million).

These numbers depend a lot on the value of volunteers’ time. My model assumed that the volunteers are people like you, the reader of this post. Most of you probably have higher incomes than average and donate a lot more money to charity than average.

My model assumes that every letter is personally written by the sender. That might not be right, because the letter-writers Bergan (2009) were probably mostly sending form letters (the paper did not specify), which means the cost-effectiveness numbers from Bergan (2009) are for form letters, not for customized ones.

You could decrease the time requirement by ~10x by sending form letters instead of personalized letters. I don’t know whether the result would ultimately be more or less cost-effective because form letters are also less impactful. My general guideline would be that it’s better to write your own letter if you’re up for it, but if not, sending a form letter is still worthwhile.

So, are messaging campaigns cost-effective?

Would I pay $58 million if that’s what it cost to pass a federal version of SB 53 or the RAISE act? I think I would. I think I’d rather spend $30 million on that than on marginal alignment research. But it’s not an obvious call and I can see arguments the other way.

$3.1 million to get a bill passed in California sounds like a great deal to me. California regulations matter less than US law, but not >10x less. Remembering, of course, that you can’t actually get a bill passed by throwing $3.1 million at a messaging campaign. But it seems like a great deal to spend a much smaller amount of money for an appropriately scaled-down impact.

Are messaging campaigns the best political intervention? I don’t know, probably not?

I haven’t made a similar effort to estimate the cost-effectiveness of other interventions. I found unusually good data on messaging campaigns, which is to say I found two experiments covering two small-to-medium state legislatures that studied only a single bill each. That’s not much to go on, but it’s better than the zero experimental studies that we often have.

It may be that it’s more cost-effective to support lobbying by a dedicated interest group with strong political connections. I spoke to one person who has done both messaging campaigns and lobbying who believes that the latter is better (under certain conditions).10 But the cost-effectiveness of lobbying is even harder to estimate than messaging campaigns.

The book Lobbying and Policy Change: Who Wins, Who Loses, and Why—which I summarized in my reading notes—found that neither PAC spending nor lobbying spending could predict political success in observational studies, although the authors expressed skepticism about this result.11 Camp et al. (2024)12 conducted four field experiments with real-world lobbyists and found that lobbyist outreach had no significant effect on legislators’ policy positions. This leaves me uncertain of what to believe, where some individuals who are involved in political advocacy believe lobbying is particularly effective, but externally-verifiable (but limited) evidence finds that it isn’t.13

(The cost-effectiveness of lobbying could be its own topic, but I’ll leave it there for now.)

Messaging campaigns look cost-effective relative to AI alignment research,14 but it’s harder to say how they compare to other types of advocacy. Separately, there’s the question of whether you, personally, should write letters to your representatives when an important issue comes up. In that case, I think the answer is a strong yes, as long as you have the spare time. If you’re limited on time, you can still sign your name on a pre-written letter, which only takes about two minutes.

How to participate in messaging campaigns

For practical guidance on how to talk to your representatives, see Talking to Congress: Can constituents contacting their legislator influence policy? That article was written by some people who, unlike me, have actually run messaging campaigns before.

Compassion in World Farming also has a guide to effective letter writing for farm animal welfare advocacy; the advice is relevant to any cause area.

I am not sure whether you should send a form letter or write out your own letter. I’m confident that personalized letters are more impactful, but they also take much longer, so it’s not clear that they’re more time-effective. I would probably suggest writing a personalized letter if you have time; but if you don’t, or if you’re not sure what to say, then sending a form letter is much better than nothing.

If you want to get involved in messaging campaigns, below are three lists of orgs who run campaigns in three effective altruist cause areas.

Animal welfare

Animal advocacy groups are well-versed in running public campaigns, and there are many ways to get involved.

- ASPCA frequently runs messaging campaigns. Its Advocacy Center lets you filter by issue (farm animals, puppy mills, etc.) and it shows a list of relevant issues that match your criteria. For example, right now it has a page on the Farm Bill, explaining how the bill will negatively impact farm animals, and providing a form where you can send a letter to your legislator.

- Mercy for Animals has a Lend Your Voice page. As of this writing, the page links to a message form where you can contact your representatives about the Industrial Agriculture Accountability Act.

- Compassion in World Farming has an “Act Now” button on its website. The direct link is here, but I’m not sure if that link will still work a month from now; if it doesn’t, go to the home page and click the “Act Now” button.

- You can sign up for The Humane League’s Fast Action Network, and you will get notified when there are actions you can take (which mostly means corporate campaigns, I’m not sure if they write letters to policy-makers).

A lot of animal advocacy orgs have useful resources; those were just a few of the ones I found.

AI safety

There is nothing particularly organized right now. I hope that there are better options in the future, but right now there is no dedicated “AI safety messaging campaign” newsletter or mailing list.

There are a few other kinds of resources, though:

- PauseAI US has a newsletter that’s mostly not about messaging campaigns. The newsletter did make a call to action on the 10-year moratorium on AI regulation; if PauseAI US runs another messaging campaign, you will probably hear about it on the newsletter. PauseAI US also has a dedicated “contact-officials” channel on its Discord.

- ControlAI has a Take Action page where you can send a message to your representatives, using either a form letter or a message you write yourself. The form letter broadly raises concern about AI existential risk, rather than being about any particular piece of legislation. (ControlAI also has a page with other ways to take action).

- The book If Anyone Builds It, Everyone Dies has an associated web page where you can write a letter to your representatives (either pre-written or written by you). As with ControlAI’s page, the letter isn’t about any specific legislation.

- PauseAI has an email builder for writing a customizable form letter.

Global poverty

I couldn’t find any orgs that run messaging campaigns focused specifically on cost-effective global poverty interventions (like the sort of thing GiveWell would recommend), but there are some orgs that focus on global poverty more broadly.

- Partners in Health has an Advocacy page where you can write Congress to support funding for global health initiatives, or sign up to the PIH Action Network.

- RESULTS has Action Alerts for writing letters to policy-makers and to newspapers.

- Catholic Relief Services has a Take Action page that includes Congressional messaging campaigns among other things.

Notes

-

Bergan, D. E. (2009). Does Grassroots Lobbying Work?. doi: 10.1177/1532673x08326967 ↩ ↩2

-

Bergan, D. E., & Cole, R. T. (2014). Call Your Legislator: A Field Experimental Study of the Impact of a Constituency Mobilization Campaign on Legislative Voting. ↩ ↩2

-

Congressional Management Foundation (2011). Communicating with Congress: Perceptions of Citizen Advocacy on Capitol Hill. ↩

-

Elkjær, M. A., & Klitgaard, M. B. (2021). Economic inequality and political responsiveness: A systematic review. doi: 10.1017/S1537592721002188 ↩

-

When I first read the paper, I found this number to be shockingly low—how could three emails cause a 12 percentage point shift in votes? But it made more sense after I did the math and realized that each New Hampshire legislator only represents about 3,000 constituents. ↩

-

Abernathy, C. E. (2015). Legislative correspondence management practices: Congressional offices and the treatment of constituent opinion. ↩

-

Stowe, L. (2023). How Congressional Staffers Can Manage 81 Million Messages From Constituents.

Note: This article did not cite an original source for its numbers. The best original source I could find was Abernathy (2015)6, which quoted 1000–1500 messages per week. ↩

-

Actually that’s slightly wrong. This number is not the mean of messages-per-outcome, it’s the reciprocal of the mean of outcomes-per-message. When calculating expected utility, it makes more logical sense to put the benefit on the numerator and the cost on the denominator. But this produces a very small number that’s hard to read, so I inverted it.

If you calculate expected messages per outcome, the result is heavily penalized by the tail outcomes where changing the outcome ends up being much more expensive than expected. This produces an incorrect estimate of expected utility (the units of utility are outcomes-per-message, not messages-per-outcome). ↩

-

I debated whether the mean or median is the more relevant number here. Philosophically, the mean is what you care about. But it seems perverse that greater uncertainty about an intervention increases how appealing it looks. Using the median instead of the mean is probably the wrong way to solve this problem, but it’s a first attempt. ↩

-

I also spoke to people who had done political advocacy and not messaging campaigns who claimed that lobbying is particularly effective. ↩

-

They hypothesized that perhaps spending by opposed interest groups cancel out, or that alliances between high-spending and low-spending interest groups create the illusion that spending doesn’t matter. ↩

-

Camp, M. J., Schwam-Baird, M., & Zelizer, A. (2024). The Limits of Lobbying: Null Effects from Four Field Experiments in Two State Legislatures. ↩

-

Under normal circumstances, I believe people over-rate personal experience, and I’m more inclined to trust the data. But in this case, most of the data comes from observational evidence which is easily confounded; I only cited one experimental study, and that study was small in scope—they only worked with three individual lobbyists. Given the weakness of the scientific evidence in this case, I don’t think it’s clearly more reliable than the contradictory anecdotes.

One limitation worth mentioning is that the experimental study tested the effect of lobbyists meeting policy-makers only one or two times. Conventional wisdom says that the value of lobbying mainly comes from establishing long-term relationships. ↩

-

I didn’t attempt to estimate the cost-effectiveness of AI alignment research. It just seems true to me that $58 million (ish) to pass a bill is worth more than $58 million of alignment research, at least on the margin. (If nobody were doing alignment research, perhaps I’d answer differently.) ↩