Can you maintain lean mass in a calorie deficit?

If you’re losing weight, does lifting weights reduce how much muscle you lose? Is it possible to entirely prevent muscle loss (or even gain muscle)?

Murphy & Koehler (2021)1 did a meta-analysis on this question. They collected experiments where the experimental groups did resistance training while eating at an energy deficit (RT+ED), and the control groups did resistance training while eating a normal amount of food (RT+CON).

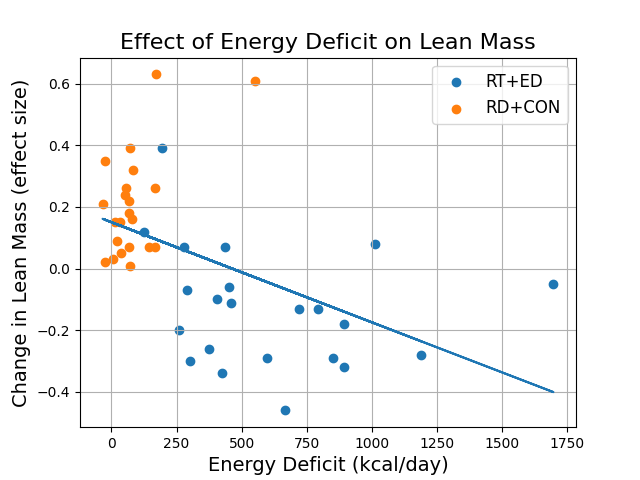

They found a strong association between change in lean mass and the magnitude of the energy deficit (slope = –0.325, p = 0.001). The meta-analysis predicts that you can eat at a deficit of 500 calories per day without losing any lean mass, but you will lose mass at a larger deficit.

(The meta-analysis also reported that participants gained strength in almost every study, even with larger calorie deficits. That’s useful to know, but I will focus on lean mass for this post.)

I should mention that what we actually care about is muscle loss, not lean mass loss. Lean mass includes anything that isn’t fat—muscle fibers, organs, glycogen, etc. Muscle mass is harder to measure. We don’t know what happened to study participants’ muscle, only their total lean mass.

Let’s set that aside and assume lean mass is a useful proxy for muscle mass.

The authors showed a plot of every individual study’s experimental group (RT+ED) and control group (RT+CON), along with a regression line predicting lean mass change as a function of energy deficit:2

But…does this regression line look a little odd to you?

Continue reading